Suzette Mayr (Literary Hub) writes about the difficulties in undertaking archival research and finding enough material to flesh out her novel, The Sleeping Car Porter (2022), based on her Bahamas-born great-great uncle. [Many thanks to Peter Jordens for bringing this item to our attention.]

I have a great-great uncle who was born in the Bahamas. His name was Baxter. He was recruited by the Canadian Pacific Railway in the early part of the 20th century to work on the passenger trains as a sleeping car porter. Young and looking for adventure, he arrived in Canada and worked for years on the trains. Sleeping car porter work was among the few decent jobs that a black man could get at the time.

Baxter is recorded nowhere in the family papers, and he likely appears in no archive, unless it’s as a criminal, named or unnamed in a police record because he was caught out for gross indecency while in the company of another consenting man, which is one of the only ways a man like him would be recorded in an official archive. Or maybe he’s not in the archives because he found the right guy, and he lived happily ever after—sometimes these things do happen under the radar. People like Baxter worked hard not to be found.

I tell you this story as truth about my ancestor even though it is 100 percent fiction. Baxter is the protagonist of my novel The Sleeping Car Porter, and I wrote him because he is the star of a book I wanted to read that hadn’t been written. I wrote him with the zeal of someone searching a family attic or closet for traces of family members whom she didn’t know existed. I made up Baxter, but I made him up because I am the only queer person I know in my Caribbean family, but not for a minute do I believe that I am actually the only queer person in my Caribbean family. I am also not the only queer black person in the history of the Canadian Prairies, where I live, and where—when I was coming out in the early 1990s—99.999 percent of the time I was the only black woman in the lesbian bar.

I know that archives are tricky places; they have been curated and controlled. It’s not a coincidence that for a long time I couldn’t find anything about queer black men in Canada like Baxter. [. . .]

Perhaps the silences in archives are deliberate—poet Nourbese Philip writes that “Silence marks lack of neither language nor identity. Rather, it is a form of communication that those who rely on the hegemonic word of private authority cannot hear.” Black Literature scholar Karina Vernon, meanwhile, writes that “black archival practices respect that the archivist is not entitled to everything, and not everything is for the public archive.”

In searching for archival evidence of a queer black sleeping car porter upon which to base my novel, I ran up against at least four possible kinds of silence: the silence of a gay man looking to stay hidden; the silence of black people not wanting to be co-opted by a white archive; the silence of the black sleeping car porters in general, as a group of men protective of their reputation; and, possibly, the silence imposed by the official gatekeepers of history who did not deem the lives of black men worthy of archival inclusion. [. . .]

A spark.

An article by Saje Mathieu, “North of the Colour Line: Sleeping Car Porters and the Battle Against Jim Crow on Canadian Rails, 1880-1920,” mentions in passing that the Bahamas is one of the places in the Caribbean where Canadian railway companies recruited black men to work as porters in sleeping and dining cars, in spite of this recruitment being outlawed. My mother is from the Bahamas! Maybe I had an uncle who answered a recruitment call. [. . .]

For full article, go to https://lithub.com/finding-black-queer-life-between-the-lines-of-history

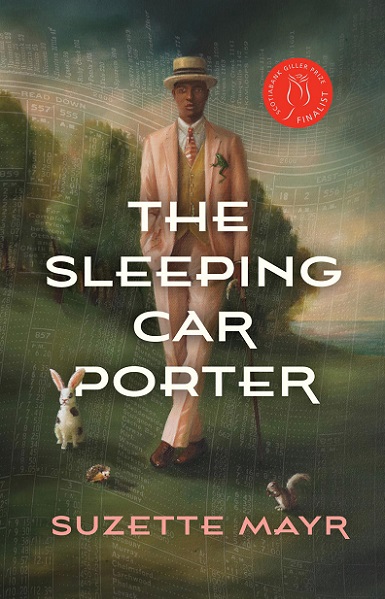

The book:

The Sleeping Car Porter

Suzette Mayr

Coach House Books, August 2022

224 pages

ISBN: 978-1552454589 (pb)

https://chbooks.com/Books/T/The-Sleeping-Car-Porter

3 thoughts on “Finding Black Queer Life Between the Lines of History”