A report by Carolina Miranda for The Los Angeles Times.

The imperial stage

There are years so formative to U.S. history that simply naming them can evoke large-scale historical events: 1619, 1776, 1865. It would be a good idea to add 1898 to that list: That’s the year the U.S. battleship Maine sankin Havana Harbor — likely due to faulty furnaces but, at the time, attributed to aggression from Spain. The incident marked the beginning of the Spanish American War and ultimately led to the U.S. seizing Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam, Spain’s last remaining colonies. That same year, the U.S. also annexed Hawaii.

In 1890, the U.S. government had declared the frontier closed. Within eight years, the country was turning its imperial ambitions to territories beyond the mainland — resulting in a bloody war in the Philippines and colonial rule that continues to this day in Puerto Rico and Guam.

A fascinating exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., explores this history through portraiture and other visual ephemera. Curated by Taína Caragol and Kate Clarke Lemay, “1898: U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions” brings together 94 objects as a way of not only exploring the U.S.’ expansionist drive but also putting a face to the people who stood in the way of its ambitions.

Namely: the populations of the conquered territories. But also Americans involved in groups such as the Anti-Imperialist League. Among these opponents of empire-building was Mark Twain, represented in the show by an affable early 20th century portrait from John White Alexander. (The dissent wasn’t all high-minded: Some members were concerned about “racial mixing” that could come out of permanent U.S. outposts abroad.)

More than half of the exhibition consists of portraits. Naturally, this includes purveyors of U.S. expansionism such as Teddy Roosevelt (painted by John Singer Sargent) and Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.), a great supporter of the Monroe Doctrine and the war against Spain. And of course, there are the military leaders who made these enterprises possible, such as Army Lt. Gen. Nelson A. Miles, who after decimating Plains tribes during the Indian Wars joined the force that invaded Puerto Rico.

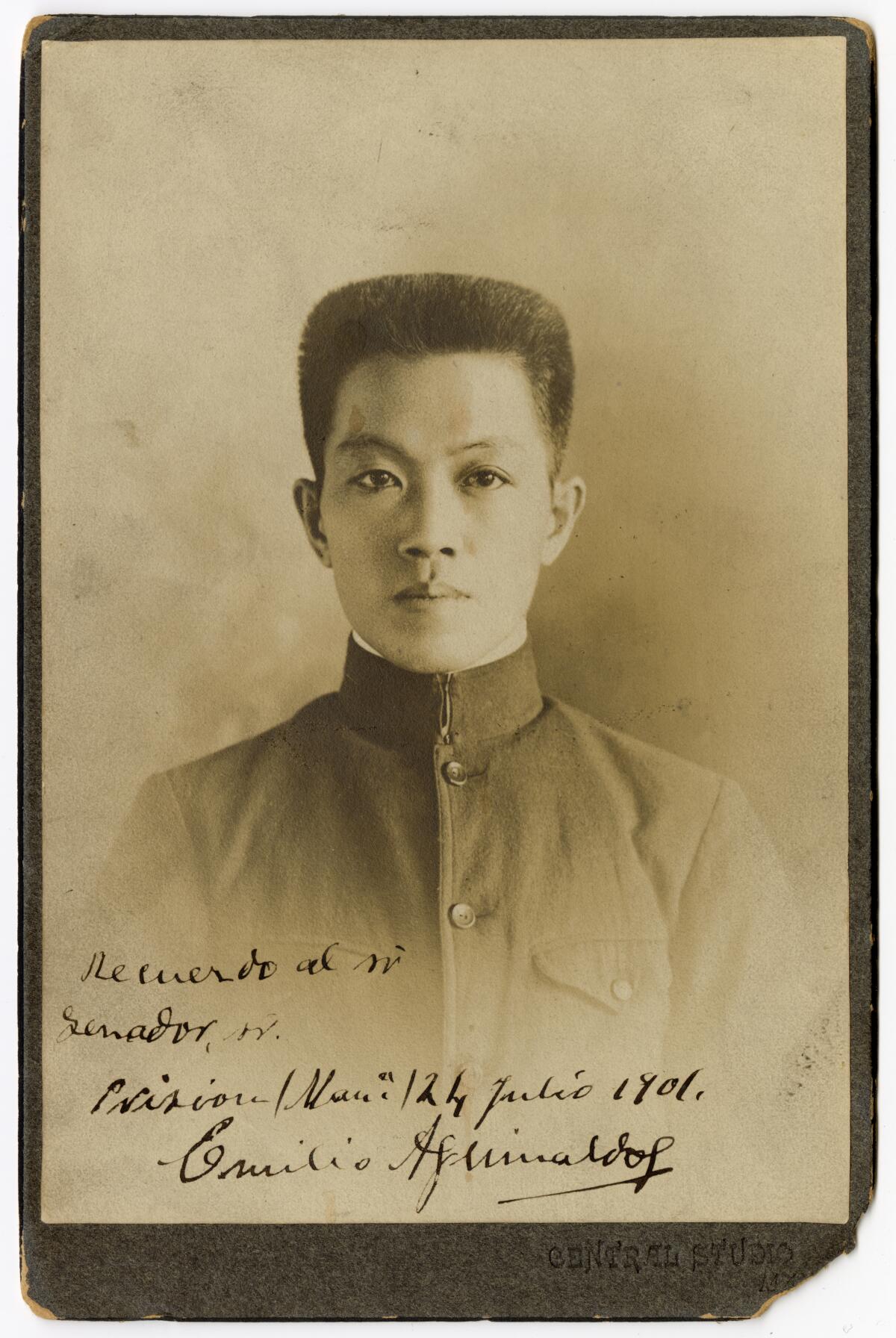

Those names and faces may be familiar from U.S. history texts, but the show is rich with portraits of people from the territories. These include a small photographic studio image of Emilio Aguinaldo, the Filipino independence leader, looking youthful and determined; and a painted portrait of Puerto Rican feminist poet Lola Rodríguez de Tío, a fierce advocate of independence.

Perhaps most remarkable is a large, late 19th century portrait of Queen Lili’uokalani, who struggled to preserve the independence of the Hawaiian people in the face of the much more powerful U.S. Navy. The portrait shows her in the regal pose of a Western monarch — a way of asserting her authority.

There are other objects in the exhibition: landscape paintings, fliers, photographs and petitions. Among the last, standouts include a missive from the Hawaiian people demanding their liberty and a letter from a group of CHamoru Indigenous people in Guam demanding representation and civilian oversight at a time when the island was ruled by the U.S. Navy. (It makes for powerful reading: “A Military government at best is distasteful and highly repugnant to the fundamental principles of civilized government.”)

I found myself absorbed by some of the weirder ephemera: a handkerchief from 1896 bearing the faces of Cuban independence leaders (including José Martí and Antonio Maceo); a board game inspired by Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. But truly unreal was a patriotic tchotchke: Roosevelt and a crew of military leaders depicted on a hand fan crafted from metallic pieces that were embossed to resemble a pansy flower. As the wall text explained, a pansy in that era could connote “a remarkable or outstanding person.”

Like everything else in American culture, imperialism has been merchandised.

“1898: U.S. Imperial Visions and Revisions” is on view at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., through Feb. 25; npg.si.edu. You can also view the objects in the show, as well as maps and other information, at 1898exhibition.si.edu.