Luis Fernando Quirós-Valverde (Wall Street International Magazine) reviews Annalee Davis’s exhibition Heartseed, shown in 2019 in TEORéTica, in San José, Costa Rica. [See previous post Review of Annalee Davis’s “Heartseed.]

The art practice of Barbadian Annalee Davis possesses the character of her research not only in terms of the cultural roots of the Caribbean context, society, and history, but also interweaves relationships at the level of what is known as the “Global South.” She frequently exhibits in museums, galleries, international projects, residencies, and other venues that enrich her artist profile.

With her show, entitled Heartseed, exhibited at the end of 2019 in TEORéTica, curated by Miguel Ángel López, she inspired estrangement, depth, poetry, which only happens when the artist becomes the essence of art and flows into it. The artist—who, when exploring the environment and history of her country, Barbados, explores is herself—manages to invest in the autobiographical element that concerns the realm of her experiences.

Her artistic research analyzes the land, the culture, the history of the Caribbean studied through gestures, non-verbal languages such as kinesics, prosemics, paralinguistics, observed through dances, conversations, and daily performances of the Caribbean. One is led to ask her how she links the context and environment of a country like hers, with what it is, or with what she likes to do, and to reflect on the value of these activators.

Annalee responds:

“I felt a deep sense of dislocation as a young person, prompting a desire to belong to something larger and different to the psychological and spatial geography in which I grew up. Education and intra-Caribbean travel facilitated understanding of the historic challenges within our postcolonial spaces, including oppressive and exclusive racial and patriarchal hierarchies that continually exert notions of supremacy or inclusion.

I am interested in the more intimate histories behind monolith and offer counterpoints to fixed constructs of the plantation as a closed site of trauma, exposing gaps in Barbados’ plantation history buried in the soil, in the public imaginary and inadequately documented in the archives.”

Superficial skin

One of the signs captured when touring the exhibition space of TEORéTica, was that of the land, both as arable organic matter or the idea of territory, with human landscape and environment, or characters of the region. They have on that skin evocative marks of the historical event that reminds us of what they were or are today, which are observed in graphics, texts written by their visual creators and researchers.

They are records on paper traces that tell us about social, racial, colonial characters, and in all this there are signs of cultural memory, which reveal the way in which they resolved their subsistence, which does not disappear despite notions of time: vicissitudes of colonization, storms that hit the archipelago, and natural tribulations, but also social and political contingencies. That skin is a step through a condition, a journey between seas and histories that know slavery and dependence on the centers (Barbados became independent from the United Kingdom in 1966).

For me, these components of the landscape are like a living museum, which remains in its memory when reading the signs: the color of the land, the character of its texture, its acidity, crops and agricultural techniques. These are aspects that affect the perception of crops, which are also interesting to recognize, since they are fruits of the planet. Why your connection with the land, with the environment, where you also organize residencies for international artists? What is the symbolism of the agriculture and the land elaborated in your visual work? What are the limits of that sacred and desired property, which is your land and culture?

“Barbados has accrued layers of agricultural and human exploitation since the early 17th century, becoming part of a larger global phenomenon now referred to as the ‘Plantationocene’ by its transformation into a plantation. Initially rich in biodiversity, the land was almost entirely deforested when the British Empire began its first ‘sugar island’ on Barbados, becoming a symbol of wealth and power for a new British nobility whose extractive economies relied on the enslavement and exploitation of foreign labour to sustain monocultural farming practices. Within that system, small plots, unsuitable for agriculture, were given to indentured labourers and the enslaved to grow food, becoming what Jamaican philosopher Sylvia Wynter calls a ‘source of cultural guerilla resistance to the plantation system’. In spite of routine horrors, these marginalised lands became sacred, manifesting as ritual spaces where the enslaved nurtured and harvested wild botanicals consumed for medicinal, spiritual and healing properties.” [. . .]

These are immemorial graphics with an idea of the fabric or embroidery, which appears not only in the drawings as a layer of sociocultural experiences, a color that tourism also sells and consumes, but there are also layers of distance, nostalgic plots for an environment that modernity demolished, erased, blocked; an artery or groove through which runs the blood that irrigates the central figure of your proposal. What is your definition of “Heartseed” and the attempt to articulate it in an exhibition?

“I appreciate your use of the term ‘estrangement’ because I think Caribbean people have been made to feel estranged from the ground beneath our feet. Given our traumatic history and the deeply inhospitable circumstances surrounding the colonial experiment by which this archipelago came into being, and given the fact that this was one of the first places in the world where its birth as an economic enterprise preceded its social evolution, we are alienated by design.

Heartseed, a slender climbing vine found as a weed growing on roadsides, its name derives from the tiny black seed that has the image of a white heart impressed on to it. The plant, popular with butterflies, is used as nesting material. I incorporate this plant as a pattern on a dress worn by a woman in the post-generative phase of her life in the ‘Second Spring’ series of drawings. We need to nest here, finally.”

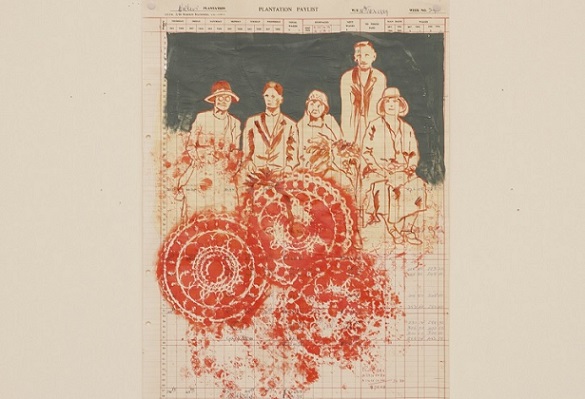

Accounting sheets like those used in the last century, for annotations and numbers, are another visible stratification in your work, conceived as a grid or framework of those complex languages of the economy, where variables such as the influence of weather, which also tend to threaten agriculture, may have a voice; or the temporality of the clock that drags notions of yesterday, today, tomorrow. All of these are like the bassline in the traditional musical rhythms of the Caribbean, a fixed pulse in which different compositional figures are mounted, but also songs and dances, sometimes they are precise contents and, in other gestures, they are notations of a vernacular dance.

That is why perhaps it moves me to consider the exhibition as marks on the skin of memory, but it is not a perpetual memory, but rather a fabric that breathes, widens or shrinks, overflows. What do the embroideries tell you? What is the symbolism of those frames, grids, or weaving?

“The Queen Anne’s Lace, both plant (Daucus carota/wild carrot) and crochet pattern have been in my work for some years. Drawing the lace-like forms suggests alternate landscapes, floating archipelagos or 18th– 19th-century porcelain and clay sherds unearthed from former plantation fields, inferring fragmented histories replete with inconsistencies and fissures. While many available archival sources are in the voice of the white male, these delicate meandering forms allude to the presence of women on the plantation, their unpaid labour in domestic spaces and shared desires for elegance and refinement. Amidst the horror, drawings of shadows cast by lace on ledger pages reference a common need for beauty, proposing that post-colonial, post-independent spaces accommodate beauty also.

Furthermore, embroidery acknowledges Edouard Glissant’s notions of entanglement and rhizomatic thought, recognising that the entanglement of our lives matters and must be considered in all its messiness. [Note: For “messiness,” the reviewer uses the term “notions of (dis)order.”] [. . .]

Excerpts translated by Ivette Romero. For full review (in Spanish), see https://wsimag.com/es/arte/61904-annalee-davis

[Photo above by Mark King: (Detail) Edith Theodocia Gertrude et al, 2016. Mixed media on ledger page, 55 x 40 cm.]