A report by Tony Bartelme for The Post and Courier.

The trial was over. The witnesses had testified, and things didn’t look good for young Anne Bonny, pirate.

It was November 1720, in Jamaica, a time of plunder. From New England to the Caribbean, pirates menaced ships. British authorities were fed up.

And Anne Bonny was about to feel their wrath.

Swift justice for sure. She and her crewmates had been caught a few weeks before off Negril, a sand-swept area on the west side of Jamaica.

But the British captain chasing them unleashed a broadside of cannon fire, taking out the pirate sloop’s boom.

Most of the crew had been hanged.

Would she go to the gallows, too?

***

Anne Bonny’s story was a seductive one. A female pirate?

Even before her trial, her name was in newspapers as far away as New England.

And over time, her exploits would generate even more attention.

In 1724, just four years after her trial, an author hiding behind a fake name published “A General History of the Pyrates.” The book was an international sensation, one that still informs and misinforms our views of pirates today.

The author based some scenes on verifiable records but likely made up other things, including tales of Anne Bonny’s life in early Charleston. Yet historian after historian plundered that book’s juicy tidbits anyway, repeating fictions until they felt like truth.

Today there are two stories about this famous female pirate, a real one anchored in facts and another story many believe is true but isn’t.

The embellished story is the one that Hollywood and pirate buffs love, the one about a freedom-loving outlaw who joins her lovers as they roam the Caribbean. This fake story is a reminder about how truth is so easily distorted — and how lies cascade through the ages.

But the true one is compelling enough without the fortified lies around it — though, like sunken treasure, it’s difficult to find.

It’s hidden amid the fabrications of historians and pirate buffs. It’s buried in archives scattered from South Carolina to Jamaica: letters, trial transcripts — documents that reveal a true tale of greed and mystery.

Our first story is from this trove.

Chapter 1 — From Charleston to the Bahamas

In the early 1700s, Charleston was a young boom town, propelled by entrepreneurial French Huguenots and planters from Barbados. The town also had a pirate problem.

For a time, merchants made good money from them. Locals “entertained the pyratts, convey’d them from place to place, furnished them with provision & liquors,” one merchant complained to British authorities. Officials who cracked down on pirates were “Enemys of the Countrey.”

And Charleston had depended on legal pirates called privateers for protection. Sometimes called “private men of war,” privateers had “letters of marque” from Great Britain — government permission to fight and raid French and Spanish ships.

But in 1713, the long war with Spain and France ended, and privateers suddenly were out of jobs. Some turned to logging and fishing. Others sailed under their own flags instead of England’s. By 1718, Charleston’s tolerance toward pirates had evaporated — especially after Blackbeard’s blockade.

Blackbeard’s real name was recorded as Edward Teach, among many other spelling variations. He had four vessels and about 400 men under his command, a small pirate navy. He’d used New Providence in the Bahamas as a base.

But Charleston was just a week’s ride north on the trade winds, and now his fleet was on the town’s horizon, intercepting ships. They robbed eight vessels and kidnapped “several of the best inhabitants of this place,” the colony’s governor, Robert Johnson, recounted in a letter.

This was serious business: Carolina planters had begun growing rice and were getting rich exporting it. They needed slaves snatched from Africa to cultivate the fields. Anything that disrupted trade was a threat.

But all was not well on Blackbeard’s ships. The pirates made a demand: medicine in exchange for the residents they’d kidnapped. Johnson complied, sending a chest that included mercury, then-thought to be a cure for syphilis.

Blackbeard returned the residents “almost naket,” Johnson wrote.

Blackbeard’s forces sailed away, and he would die in North Carolina in a battle later that year. And much later, in 2015, archaeologists would find metal urethral syringes with mercury in the sunken wreck of his flagship, the Queen Anne’s Revenge.

But Blackbeard’s blockade was a pivot point in Charleston’s early history. Afterward, South Carolina’s leaders organized pirate-hunting missions and soon caught scores. They tried and hanged about 50 in 1718 alone. They strung them up on what today is East Bay Street, overlooking the harbor. Left to waste away in the sun, their decaying bodies signaled to incoming ships that pirates were no longer welcome in South Carolina.

Many pirates would make their way to New Providence in the Bahamas.

Among them was a woman named Anne Bonny.

Chapter 2 — A pirate spree begins

By the summer of 1720, her name was in The Boston Gazette, though she’d been identified then as “Ann Fulford alias Bonny.” The mention came in a proclamation by Woodes Rogers. A one-time privateer himself, Rogers was now governor of New Providence, an island that had been dubbed “a nest of infamous rascals.”

Before Rogers’ arrival, New Providence had no government. It was a place where a man only did “what’s right in his own eyes,” one observer reported to the crown. Pirates spent “riotously” what they “wickedly got.” Between 500 and 1,000 pirates shared their New Providence hideout with about 200 residents.

A second official reported: “The settlement now consists of those who have lately been pyrating” mixed with prostitutes and old inhabitants who were so poor “they want almost everything.” Another complained that pirates “create disorders in that island, plundering the inhabitants, burning their houses, and ravishing their wives.”

It was in this pirate nest that Anne Bonny somehow joined a gang led by John Rackam.

Rackam “took with him 12 Men and Two Women,” a report in The Boston Gazette said. They stole a sloop from New Providence called the William, which had four cannons and two “swivel guns” — swivel guns were small rail-mounted cannons that could be turned quickly toward targets. With these arms, the “Pirates Swear Destruction to all those who belong to this island,” The Boston Gazette reported.

Rogers announced that Rackam’s crew had already robbed another boat near the Bahamas and a third on its way from South Carolina. He identified eight people, including Rackam, Bonny and a second woman, Mary Read.

Forthwith, Rogers proclaimed, all were “Enemies to the Crown of Great Brittain.”

***

The new governor of New Providence in the Bahamas proclaims John Rackam, Anne Bonny and others as pirates in The Boston Gazette, January 31, 1721.

Within months of Rogers’ proclamation, Bonny and her crewmates had been captured, but not in their base in the Bahamas.

They’d sailed deeper into the Caribbean, toward Jamaica, robbing seven fishing boats on the way. Off Negril, a British captain named Jonathan Barnet caught them in a secluded cove. The crew had been drinking what a witness would later describe as “a bowl of Punch.”

Barnet had hailed the pirate sloop: Who was its leader?

“John Rackam from Cuba,” came the response.

Barnet ordered him to surrender. Rackam’s crew answered with a swivel gun.

But Barnet was ready and blasted away with his own cannons, and soon Rackam’s crew was in his custody.

Nine crew members, including Rackam, were tried and taken to Gallows Point. They’d been placed in a metal cage called a gibbet. They were then left to hang “for a publick Example, and to terrify others from such-like evil practices.”

Now, the judges would hear the women’s cases.

Chapter 3 — Pirate women on trial

The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates

The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates is the official account of the trials and convictions of Anne Bonny, Mary Read and her crewmates.

Their trial began on Nov. 28, 1720. Jamaica’s elite gathered in a courtroom in Saint Jago de la Vega, later known as Spanish Town. Among the judges and presiders was Nicholas Lawes, a British knight and governor of Jamaica.

An official account of the trial survives. According to that document, Anne Bonny and Mary Read were led to the bar, a railing in the front of the courtroom. The court record identified Bonny and Read as “spinsters” late “of the Island of Providence.” Bonny also had another alias, “Bonn.”

How did they plead?

“Not guilty,” the women answered.

The testimony began.

***

Thomas Spenlow was one of the first witnesses.

Spenlow owned a schooner that was off northern Jamaica when Rackam’s sloop attacked. Spenlow surrendered, and Rackam’s crew took the ship, along with 50 rolls of tobacco, nine bags of Pimento and 10 slaves. He told the court he saw both women aboard.

After Spenlow, two Frenchmen were sworn in, along with a French interpreter. They told the court they’d been hunting wild hogs on the shore of Hispaniola when Rackam’s crew kidnapped them. Sailing with the pirates, they witnessed raids and saw Bonny hand gunpowder to the crew when needed. The women wore men’s clothes when the pirates attacked ships and women’s clothes other times.

They were “very active on Board, and willing to do any Thing” and “did not seem to be kept or detain’d by Force, but of their own Free-Will and Content,” they told the judges.

Next up was Thomas Dillon, owner of the Mary and Sarah. He said his ship was anchored off the northern coast of Jamaica when “a strange Sloop” sailed close and then fired.

Dillon and his crew piled into a small boat and paddled toward shore for help. But someone on Rackam’s ship shouted that they were English pirates and that Dillon had nothing to fear.

Dillon accepted the crew’s invitation to join them. But on board he saw Anne Bonny with a gun in her hand. Both women “were both very profligate, cursing and swearing much, and very ready and willing to do any Thing on Board,” Dillon told the court. The pirates then stole his ship.

But some of the most damning testimony came from a woman named Dorothy Thomas.

Thomas said she was in a dugout canoe filled with provisions when the pirate sloop closed in. Rackam’s crew cleaned out the canoe, and the women took part in the robbery.

She told the court that both wore men’s jackets, long trousers and had handkerchiefs tied about their heads. Each carried pistols and machetes. They swore at the men, urging them to murder her to prevent her “from coming against them.” She told the judges she knew they were women “by the largeness of their Breasts.”

***

When the testimony was over, the court asked Bonny and Read whether they had witnesses or a defense.

No, they told the court.

The verdict was unanimous: guilty of “Piracies, Felonies, and Robberies committed by them, on the High Sea.”

Nicholas Lawes, the Jamaican governor, asked whether they had anything to say that might persuade him to spare their lives?

No, they answered.

Lawes then said: “You Mary Read, and Ann Bonny, alias Bonn, are to go from hence to the Place from whence you came, and from thence to the Place of Execution; where you, shall be severally hang’d by the Neck, till you are severally Dead.”

Chapter 4 — A second chance?

Nicholas Lawes and the judges in Jamaica held more pirate trials in the coming months, including one for Charles Vane. Vane also has used New Providence as a base and took ships off Charleston.

All were hanged at Gallows Point — all but Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

After Lawes sentenced them to death, Bonny and Read suddenly told the court they “were quick with Child,” the trial account said.

They asked Lawes to set the sentence aside.

Lawes agreed until an “inspection should be made.”

Later, the answer: Yes, they were pregnant.

Lawes suspended their sentences.

Mary Read is believed to have died some months later, at about the time she would have given birth — and that she likely is buried in Jamaica.

Anne Bonny’s fate is more mysterious.

It’s at this point in her story where the document trail vanishes and historians and pirate buffs pave new ones.

Did she have a child? Did she move to Charleston and marry?

So begins our second story, which isn’t about Anne Bonny as much as it is about the yearning for a good yarn — true or not.

Chapter 5 — The story about the story

It begins in 1724.

That year a London publisher printed “A General History of the Pyrates” with the intriguing subtitle, “With the remarkable Actions and Adventures of the two Female Pyrates Mary Read and Anne Bonny.”

Its author was someone named Captain Charles Johnson, though no evidence has surfaced that a writer by this name existed. Pen names were common then, and much later and with no hard evidence, a historian pinned the work on Daniel Defoe, who’d written “Robinson Crusoe.” The historian’s case was based on Defoe’s interest in pirates. This was thin ice, but historians skated on it anyway until encyclopedias cited Defoe as the author.

More recently, historians have suggested that a London publisher named Nathaniel Mist penned the book. Mist ran a weekly newspaper that often ran stories about pirates, and he was a former sailor. But, again, evidence is circumstantial at best.

More clear was the book’s impact. It portrayed pirates as symbols of villainy and freedom — daring and violent outsiders flouting sexual and legal restrictions of the day.

The book was a huge success, today’s equivalent of an international bestseller. It sold so well the author wrote a second edition, advertising its “considerable additions.” He included new details about Bonny and apologized for the price increase. The author also acknowledged that some “gentlemen” had challenged the first edition’s accuracy — “that it seems calculated to entertain and divert.”

So be it, the author wrote: If readers found it entertaining, “we hope it will not be imputed as a Fault; but as to its Credit.”

It would shape the world’s views about pirates for the next three centuries.

Chapter 6 — A Charleston connection?

The Captain Charles Johnson account about Anne Bonny began in Ireland, where her father was said to be a lawyer with a wandering eye. The author never named him but said the father had an affair with a servant and “play’d the vigorous Lover.” The story went that his wife grew suspicious and accused the maid of stealing spoons.

The maid ended up in jail, the author claimed. But when people learned she was pregnant, she was released. She gave birth to a girl she named Anne. The whole affair eventually was exposed, triggering a scandal that ruined the lawyer’s business. As a result, Anne’s father was said to have moved to “Carolina.” In the late 1600s and early 1700s, this usually meant Charleston.

There in the new colony, the father practiced law but became a merchant and rich enough to buy a “considerable plantation.” But Anne was said to have a fiery temper. And as a young woman, she married a sailor named James Bonny against her father’s wishes, according to the Captain Johnson account. Together, Anne and James Bonny sailed to the Bahamas.

The author claimed that in this notorious pirates’ nest, Anne fell in love with John Rackam. Anne was “not altogether so reserved in point of Chastity,” Captain Johnson wrote. Rackam spent large sums of money on her, and so she decided to run off with him and rob ships.

At some point during the raids, Anne Bonny fell for another crew member named Read — but eventually discovered Read was a woman, Mary Read. (The Captain Johnson book has an equally elaborate background story for Mary Read.)

Rackam allegedly saw the two become friendly. Still thinking Read was a man, he “grew furiously jealous, so that he told Anne Bonny he would cut her new Lover’s Throat.” She then told Rackam that Read was a woman, which seemed to quiet things down.

The Captain Johnson account also appears to be the origin of Rackam’s nickname, “Calico Jack,” for his supposed fondness for calico clothing. Neither the trial transcripts nor newspaper reports, which included aliases for other pirates, ever mention this nickname.

The Captain Johnson tales hew closer to official trial records when describing the pirates’ spree in the Caribbean. But the author added many flourishes. Of the women, he wrote: “No Person amongst them was more resolute, or ready to board or undertake any Thing that was hazardous.”

And after her conviction, he offered one last plot twist, also unverified: Her supposedly prosperous father from Carolina was well-known to planters in Jamaica, who were inclined to show her mercy — until “an ugly circumstance” happened just before Rackam was hanged.

“By special favour,” Rackam was allowed to see her one last time. But Bonny is said to have lectured him instead of offering comfort, saying: If he’d “fought like a Man, he need not have been hang’d like a Dog.”

The author concluded Bonny’s tale with a mention of her giving birth in Jamaica.

“What has become of her since, we cannot tell. Only this we know, that she was not executed.”

Chapter 7 — Fiction as fact

Seduced by the elaborate Captain Charles Johnson yarn, historians and others later played a long game of telephone, taking unverified details as fact and adding new ones with each telling.

In 1725, an author suggested without documentation that Anne Bonny and Mary Read were lesbian lovers. In the 1960s, a writer named John Carlova wrote “Mistress of the Seas,” which Carlova said was based on extensive archival research in the United Kingdom and Jamaica.

He introduced names of people said to be her parents: William Cormac and Peg Brennan. He wrote that Anne remarried, had at least eight children and moved to Virginia, where she died. He did not cite or include specific sources backing up these claims. Many scenes in the book also have the kind of dialogue found in detailed diaries and letters — or the imaginations of novelists. So far, no evidence has been found to support this dialogue. Carlova is now deceased.

But other historians picked up where he left off. In 2000, Tamara Eastman and Constance Bond wrote a book that identified Bonny’s parents as William Cormac and Mary Brennan. The authors claimed that Bonny married a man from Virginia in 1721 and lived to age 84.

David Cordingly, a noted pirate historian, echoed those details in several books, naming James Burleigh as the man Bonny married.

He included this information in an entry for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, a reference book that describes itself as the “national record of men and women who shaped British history.” Cordingly cited “Family papers in the collection of descendants” as his source for Bonny’s birth and upbringing.

Today, many of these details are in Bonny’s Wikipedia entry. They’re cited as true stories in books and magazines, such as an article by Karen Abbott in Smithsonian magazine. In that story, Abbott parrots a mix of unverified claims by Captain Johnson, Carlova and Eastman — and also describes Bonny as a “pirate queen.” Abbott did not respond to interview requests.

A closer look at these stories show they fall apart like poorly tied knots.

Chapter 8 — No evidence

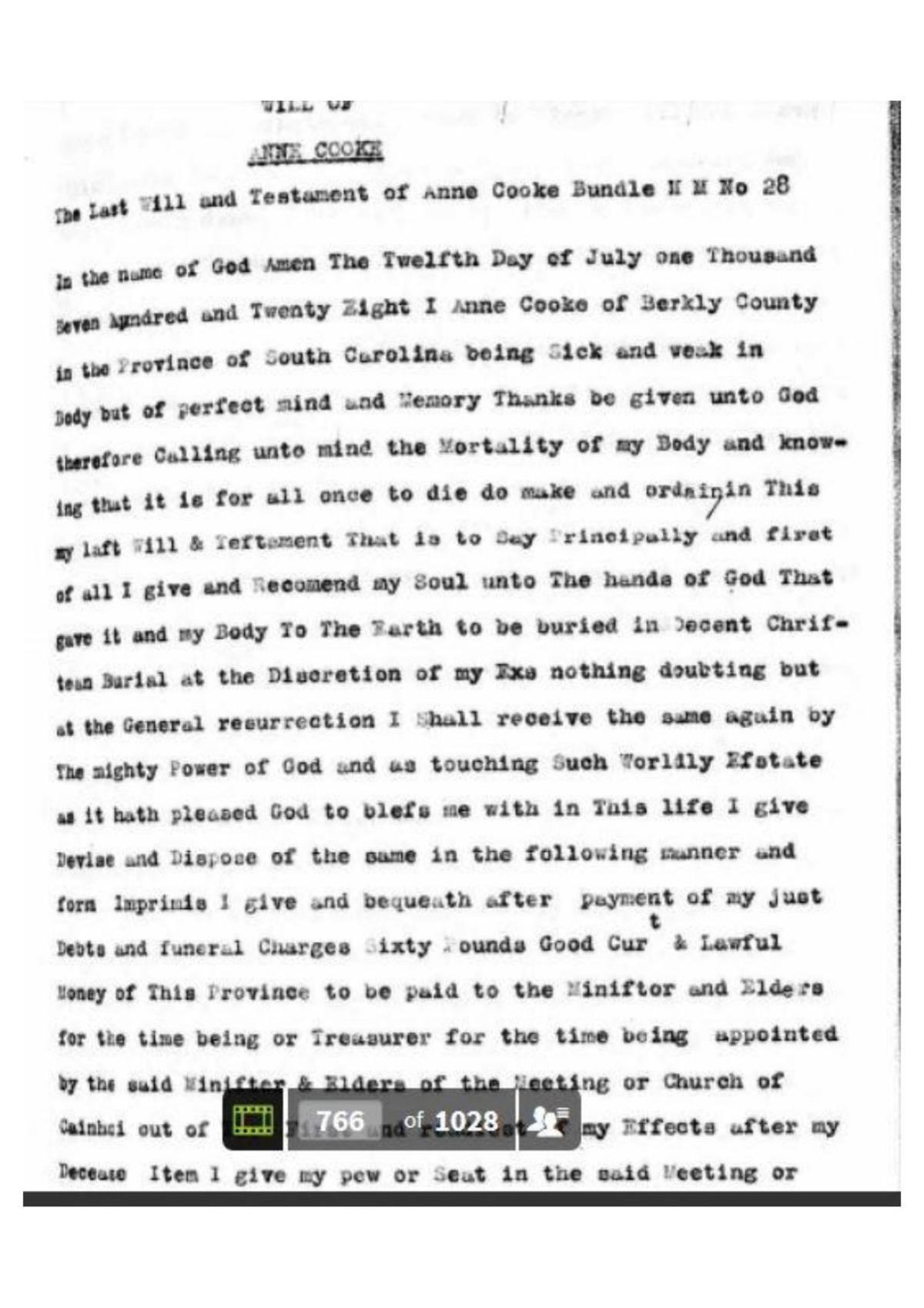

William Cormack 1735 grant

William Cormack 1735 grant

Prominent early Charleston residents left extensive paper trails in deeds, wills, land records, church rosters and newspapers.

Yet a search of these and other archival documents revealed no one named William Cormac in South Carolina during the late 1690s and early 1700s. This is a surprising omission for someone described as a well-to-do planter.

In 1735, 15 years after Bonny’s trial, a William Cormack (with a k) received a grant of 50 acres on the Pee Dee River from the king of Great Britain. But there’s no evidence connecting the Cormack that received this relatively small tract to Anne Bonny.

The Anne Bonny paper trail leads to other dead ends.

In 1728, an ill and weak grandmother in Berkeley County named Anne Cooke wrote a will. In it, she mentions her daughter Ruth, who was married to a man named Thomas Bonny. They, in turn, had a daughter, Anne Bonny.

In her will, Cooke gave Anne Bonny a slave named Lucy, a feather bed and other items. But she added an intriguing restriction: Anne and her other granddaughters would inherit these things if “they do not Marry with Sailours.”

But there’s no evidence connecting any of these people to anyone named Cormac or the Anne Bonny tried in Jamaica. Also, Anne Cooke’s reference to a granddaughter named Anne Bonny challenges the notion that Anne Bonny married and ran off with a man named James Bonny, or that she later re-married another man named James Burleigh. No documentation could be found in state and local archives about these two men.

In an email, pirate historian David Cordingly said that many of Captain Charles Johnson’s “facts check out with documented sources,” but he’s “always been extremely dubious about much of his material about the female pirates, particularly their early lives.”

He said that while doing research, Tamara Eastman contacted him and showed him letters and a family Bible.

These documents suggested Bonny’s father had found a way to spare her from punishment in Jamaica and taken her back to Charleston. They also seemed to show that she married a man named James Burleigh. Cordingly said he included this information in a book about women sailors, hoping that it would generate more leads.

Cordingly said that, until contacted by The Post and Courier, he hadn’t heard of anyone trying to pin down whether a William Cormac lived in South Carolina in the early 1700s. Advised that no documentation could be found, he said: “I guess we will have to discount the information I got from Tamara Eastman.”

In an email, Eastman said that about 30 years ago she found some documents with a woman’s name “that MIGHT have been The Anne Bonny, but it was never proven as such through any records.” She said she lost many records in a fire. “I doubt you’ll ever be able to fully pin down anything.”

Chapter 9 — Myth-busting

On a warm fall morning, Eric Lavender walked down a cobblestone street in Charleston, a city that has long guarded its historical authenticity. On his shoulder was a parrot named Capt. Bob. Lavender was dressed in pirate garb. He does pirate tours that are rooted in specific and citable historical records. He leans on Captain Charles Johnson’s questionable account in 1724 for some of his stories, but with caveats about its accuracy.

People have a deep thirst for the Hollywood version of pirates, yet Lavender takes pains to bust some myths.

“Pirates probably didn’t say ‘Arrgh,’” he said, noting that saying “Arrgh” probably came from early Hollywood movies.

Pirates also didn’t “walk the plank” or likely use hooks and pegs for prosthetics.

“They would have been too unwieldy to use.”

Anne Bonny’s story is in strong demand, given the rarity of female pirates and the swashbuckling descriptions from the Captain Johnson tale. But documenting her story, he said, is “like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.”

***

Meanwhile, incentives to tell tall tales are powerful, and the pirate entertainment complex is in full sail. The Pirates of the Caribbean movies have hauled in $4.5 billion. The character Anne Bonny was featured prominently in the Starz series “Black Sails.” Hundreds of pirate festivals are held across the world. Michigan lawmakers passed a resolution making “International Talk Like A Pirate Day” an official holiday.

Then again, true or not, who doesn’t love yelling “Arrgh”? Or a kid with an eye patch saying “Ahoy matey!”?

But embellishments have consequences, said David Fictum, a historian who has analyzed the facts and myths surrounding the Anne Bonny story.

“I can’t emphasize enough that some historians are just as culpable as fiction writers for perpetuating the mythos.”

Exaggerations and outright fictions create layers of lies that overwhelm the true story, he said. Mythmaking diverts attention from other important but less flashy stories, such as how industrious women set up their own sewing shops to support mariners.

“Allowing embellishments makes historical studies practically meaningless,” Fictum said.

Nearly three centuries after Anne Bonny’s trial, we know that a woman named “Anne Bonny” was alive in the early 1700s, that some people called her “Ann Fulford” and “Bonn,” that she lived in the Bahamas for a time and joined a pirate crew.

We don’t know whether she ever lived in Charleston, who her parents were, whether she married a man named James Bonny, her true role aboard the pirate sloop, what her relationships were with Jack Rackam and Mary Read, and whether she ever was released from the Jamaican prison.

So her story lives on in two alternate universes: a true tale rooted in authentic documents and another layered in fiction and speculation.

Only history will decide whether the second plunders the first.

Epilogue: Why we’re telling a pirate story in 2018?

A mural in a Folly Beach children’s park inspired this story.

The park is tucked away in the center of the island, next to the town’s water tower. The mural is painted on a concrete wall across from the playground. It shows a fierce Anne Bonnie and “Calico Jack” about to engage in a fight.

We thought a light-hearted look at female pirates would be fun for readers. But the more we dug into it, the more cracks we found in the Anne Bonny story so often featured in history books.

This raised fresh questions about the use of history for entertainment, and the importance of setting records straight.

Charleston has long leaned on its historical authenticity to set it apart. Its motto is “She guards her temples, customs and laws.” So the story about Anne Bonny eventually evolved into one about truth — how writers can shape and sometimes distort things soon after events take place, and how these distortions are magnified over time.

This makes the Anne Bonny saga as relevant today as it was in 1724, when a person using the pseudonym Captain Charles Johnson penned his first embellishment. Truth matters — then and now.

This story is copyrighted by The Post and Courier and is wholly owned by The Post and Courier. Please remove this content from your site immediately or we will have to take legal action. Thank you. — Mitch Pugh, Executive Editor, The Post and Courier

LikeLike

Thieves stole this story from The Post and Courier!

LikeLike

A great deal of work went into producing this piece for The Post and Courier. It is wholly unethical for this site to steal and repurpose this work for its own benefit. Please remove immediately. – Glenn Smith, special projects editor, The Post and Courier

LikeLike