This article by Tony Fraser appeared in Trinidad’s Guardian.

“On my return to T&T (1970) after five years in Canada at the University of Alberta, I was stunned by the “light” here and I knew right away I had to capture this. Tied into this were my childhood experiences with my father through the countryside and the coasts; I wanted to capture those scenes and their light and in watercolours that fascinated me 60 years ago in the Central Library.”

Hinkson reaches for a definition of that hard to define, elusive quality that describes “light”; to do so he paraphrases what Derek Walcott as art critic said of his work during the poet/playwright’s years of writing for the Trinidad Guardian: “I am not talking about light and shade or shadow and darkness and colour and so on, I am talking about where the colour resonates below the surface…where the darkest dark shines.”

To the plein air (landscape) artist, light is an elusive challenge: “It’s not just brightness, it’s a quality of reflected heat and glare combined, which varies with the time of day and year and the environment. So even in the dark purples there is still a sense of a vibrating light coming through,” says Hinkson.

Next time you view a Hinkson watercolour painting, look beneath the surface for the light. It may even be that the artist is encouraging us to dig beneath the surface for deeper meaning; for some truth about our existence.

In the same breath, however, Hinkson urges that his work simultaneously celebrates the recognisable images depicted and the shared emotions they evoke; many of those images came out of his early years in Cobo Town.

For the uninitiated in the social and physical geography of Port-of-Spain in the 1930s into the 1970s, Cobo Town was that portion of the old city from Richmond and Duke streets, going south to Charles, Sackville and London streets and stretching west to Wrightson Road. On the south-east of Cobo Town was Donkey City, and on its north-west the more gentrified homes. The name came from the vultures that feasted on the waste of the fish market in the area.

From the family home situated at Richmond and Charles Streets, Hinkson and his family experienced Red Army/Merry Makers on J’Ouvert morning, Pretender (Preedie) the calypsonian, and the “bad-johns” of the era who protected the steelbands and the community from those who would venture into the territory.

For the boys growing up there, both from the middle and barrack yard social classes, cricket and football in the savannah topped the agenda of play. Occasionally, they would “tief” a chance to play in Victoria Square, where games were banned in a black and white sign, but where berry war was compulsive given the millions of yellow berries on the ground waiting to be stoned by boys one against the other.

“Based on my background in Cobo Town and our genuine camaraderie with the poorer boys, my awareness of how the disadvantaged lived and even my admiration for how they survived inspired my predilection for capturing plein air (the landscape), the light, and the architecture of this environment, the barrack yards and also the grander houses of the plantation type.”

A commission he received from the government in 1982 allowed Hinkson to capture traditional architecture of town and country. It resulted in 100 drawings in conte crayon and watercolours which are in the National Museum and government offices; the contours of the paintings do not follow the precise lines of the architecture, but like his main works of the time, are closer to that of the impressionist school of painting in which lines and shapes are more freely rendered to suit the painter’s impression of reality.

It is a style that Hinkson adopted early in his career after the French Impressionists painters of the last quarter of the 19th century: Claude Monet, Paul Cezanne and others who broke with the conventional painting styles and subjects and adopted bright colours and light of the outdoors in their landscapes.

A feature of Hinkson’s work is how he allows the viewer to see beyond the obvious; like the painting of the fisherman at his stand at the entrance to Pigeon Point. On the canvas, Hinkson draws our attention to the skillfulness and discipline of the fisherman.

“So I am saying, don’t underestimate that man, he is doing a great job, he’s skillful, humble and he is valuable.”

Hinkson tells of an outdoor experience in John John of asking for permission to draw a particular house and receiving a perfunctory/offhanded sign to go ahead from a stern-looking, silent young man.

“The man eventually came out, bare-backed, and with scars now visible on his face, to hold an umbrella over me on a hot Saturday afternoon,” says Hinkson. Clearly, the man appreciated that a painter capturing his world had value and had to be protected.

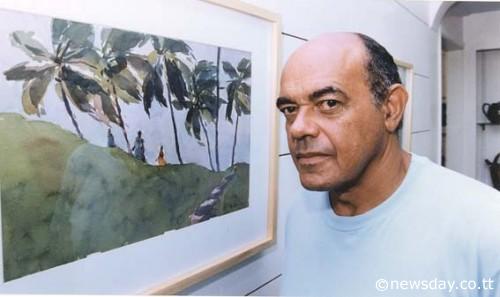

Jackie’s talent for painting first emerged and was developed at Queen’s Royal College in the 1950s. There he became associated with another aspiring artist, one Peter Minshall: one became a master designer of the street theatre—“the mas”; the other the premier watercolourist of T&T.

Painting in watercolours, notwithstanding its distinguished tradition going back more than 150 years, has been and, to some extent, continues to be viewed with some skepticism and non-acceptance here in T&T—it’s not oil on canvas, not the “real thing,” according to the skeptics. But contrary to this view, painting in watercolours is considered the most demanding genre: “It’s an unforgiving medium.

The paper can take only so much layering of paint, and the artist has very little room for making changes as opposed to painting in oil which can be adjusted time and again to get the right colour, tone and feel,” says the watercolourist.

Hinkson’s range of subject matter has expanded over the decades. His keener observation of his society, of human conduct, of growing individualism, and the changing role of women are now more vigorously reflected in his landscapes.

“I decided I had to make the human figure more central to my work, and I needed to work larger so I needed to revert to oils; that was some-time in the 1980s and I produced a number of very large paintings, held an exhibition at QRC where the human figure played a much greater central role.”

Does Jackie Hinkson, after 55 years of painting, still get challenges from his work?

“What! Constantly; it’s a source of challenge. I still see it as hard, hard work; it frustrates me. Occasionally I feel good about a finished work. But I intend to continue painting, I can’t do anything else. I know that as long as I am aware of what’s happening around me, I would be driven to express and to reflect that in my work; apart from family, that’s my life.”

His life has not been the romantic one of the artist creating in fits and starts and living on the edge. Instead, brought up in solid family circumstances, Jackie has been the responsible family man. He has worked and planned for a quality of material life with and for his family.

As to his reflections on our civilisation, like many, he is depressed by its commercial vulgarity, depicted for instance on the billboards scattered across the landscape, and many other aspects of contemporary society that reflect a growing inhumanity.

“We need to expose young people to the appreciation of the arts in their education, have more of them become artists, musicians, writers, or at least to become more aware of the human condition,” the artist feels.

On average, Hinkson continues to work at least five hours a day, whether painting, sketching, sculpting or even more recently, exploring the possibilities of digital art on his iPad. Does he feel satisfied with his achievements over the decades?

“I always feel I could have done it better; I could have done more, and that there is more to be done; but I am fearful that I won’t get it done.”

I find reading the description of Corbeaux town interesting, reminding me when we used to swim in Harbour scheme, as it was then called. What I don’t like is the expression of ‘poor people’

LikeLike

WHERE IS THE NAME OF THE ART COME ON BR MORE SPECIFIC

LikeLike