A fellow writer recalls Algarín, who once wrote that the poet was “the philosopher of the sugar cane that grows between the cracks of concrete sidewalks.”

A report by Ed Morales for The New York Times.

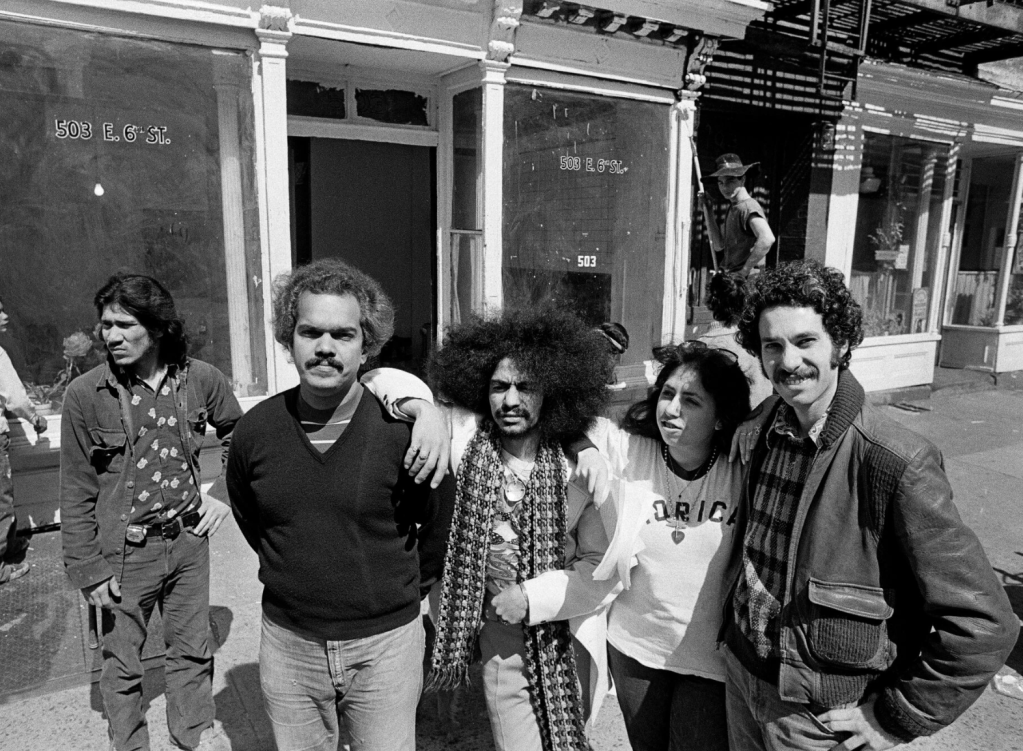

Back in 1973, often remembered as the bad old days of the Lower East Side, Miguel Algarín, focusing on the light he saw shining from an emerging New York Puerto Rican community, began hosting a series of informal poetry readings in his apartment on East Sixth Street that brought together poets, theater types andmusicians.

The gatherings soon outgrew his living room. Together with several contemporaries, Algarín went on to found the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, which opened down the block from his apartment in a former Irish bar on East Sixth Street. A new literary movement was taking shape.

Algarín, who died on Monday at age 79, helped forge that movement, playing a central role in creating Nuyorican poetry, and in popularizing the term Nuyorican to describe the bilingual, bicultural reboot of Puerto Rican-ness blossoming in the neighborhoods of New York.

Born in San Juan and raised on the Lower East Side, Algarín attempted to merge the highbrow culture of his working-class parents with a Rabelaisian Everyman rebellion from below. He had a fearless sense of pride and was a champion of the underprivileged. The passion for Shakespeare he displayed as a professor at Rutgers University seamlessly fused with the Africanist urgency of his own poetry, producing a body of work that reflected his fluid use of Spanglish and shifting sexual identity.

That first incarnation of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe acted as the headquarters of a generation of young poets who broke from the folkloric stereotypes of islander passivity to be reincarnated as “Super Fly” rhymers. The path was blazed by a cadre of poets including Miguel Piñero, whose play “Short Eyes” was championed by Joseph Papp’s Public Theater; Pedro Pietri, who read his epic poem, “Puerto Rican Obituary,” in 1969 when the activists of the Young Lords occupied a church in Spanish Harlem; Sandra María Esteves, who was one of the pioneering women of the movement; Lucky Cienfuegos; and Jesús Papoleto Meléndez.

In an era that would soon give birth to hip-hop, the Nuyoricans embraced a declaiming style that was shaped by contemporaries including The Last Poets; many were influenced by Ntozake Shange, one of the cafe’s founding poets, and her Obie-winning play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf.” The cafe also had visits from beat writers, including Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, whose “pale, inflected voice,” Algarín once told me in an interview, “still could reach us through his humor.”

“The poet blazes a path of fire for the self. He juggles with words. He lives risking each moment. Whatever he does, in every way he moves, he is a prince of the inner-city jungle. He is the philosopher of the sugar cane that grows between the cracks of concrete sidewalks.”

When I read those words, written by Algarín in his introduction to “Nuyorican Poetry: An Anthology of Puerto Rican Words and Feelings,” in a corner of St. Mark’s Bookshop, it was as if time had stopped for me. I had become fascinated with beat poetry in high school and college, once daring to read the work of Amiri Baraka at a campus cafe, but this was life-changing. Here was that same spirit of rebellion and anarchic emotion, translated through a code-switching working-class eloquence, that spoke to me, and to a generation of New York-bred Puerto Rican migrants.

In that 1970s period of identity-based nationalism, as sensuous salsa mined nostalgia while the Young Lords reveled in the militancy of the present, Nuyorican poetry looked toward the future — or, as Algarín wrote, “the street burning up with its vision of times to be.”

I didn’t get to meet Algarín until years later, when I took part in the Nuyorican Cafe’s rebirth in the 1990s, at its new home on East Third Street. I expected to meet someone more like Piñero, whose wiseguy Spanglish hipsterism had defined the genre for me. But if Piñero was a Lower East Side Jean Genet, Algarín’s bellowing voice rang down on me like James Earl Jones mixed with James Baldwin: imperious yet somehow vulnerable.

His first lesson was about breathing and performance, when I had expected a line-edit. And while he seemed ambivalent about my poetry, he accepted me into his community, like the prince of the Nuyorican kingdom that he was.

That second phase of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe had begun after Piñero, a tragic figure who was very close to Algarín, died in 1988. It was during Piñero’s wake at a funeral home on the Bowery that Algarín, already reeling from the earlier death of Cienfuegos, was approached by Bob Holman, who had been working with the St. Mark’s Poetry Project.

“Bob whispered, ‘Mike is saying, wake up, reopen the cafe,’” Algarín later told me in an interview. The cafe reopened a little more than a year later, and this time, things would be different.

Under the direction of Algarín and Holman, the cafe expanded its mission, reflecting a time of change in the gentrifying East Village, as well as a new era of identity politics. Holman brought in the idea of a competitive poetry slam, which created packed houses and caught the attention of MTV’s “Real Life,” which featured Kevin Powell, a cafe poet, as one of its original cast members. No longer an ethnic-specific venue, the Nuyorican Café embraced proto-hip-hop African-American poets, N.Y.U.-ish white poets, feminist poets and L.G.B.T.Q. poets.

Today, spoken word theater is universal, and the legacy of Algarín and the generation that founded the Nuyorican Poets Cafe has stretched across the globe.

In a sense, Algarín — who tested positive for H.I.V. in the late 1980s, writing, “Can it be that I am the bearer of plagues?” in his 1994 poem “HIV” — was the ultimate survivor, outliving most of his contemporaries, and maintaining a quiet presence on the Lower East Side, even as the cafe became a nonprofit corporation with a new board of directors. With a seemingly endless expression of varied sexuality, much of his work centered on the body.

As Ishmael Reed wrote in his introduction to the volume of poetry “Love Is Hard Work,” Algarín “believes with García Lorca that the poet is the professor of the five senses.” Ennobled by an unbridled spark that crossed borders, he left a legacy that will live long into the future, his brash street edge now at rest alongside his gentle love for his people.

there is a pleasure in living,

there is no shame in being

full of love — From “Sunday, August 11, 1974”