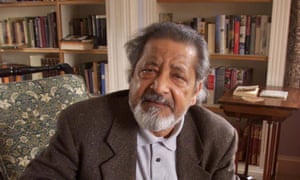

The greatest literary virtue of the Trinidad-born writer VS Naipaul, who has died aged 85, was instant readability. He constructed clear, irreducible sentences, and marshalled them into single-minded paragraphs. His control of language and the rhetoric of his novels were such that he could persuade you into belief even when his truths were only partly true.

Naipaul, the winner of the 2001 Nobel prize for literature, was regarded by many as the greatest novelist of his time. In his early fictions he trusted description, character, dialogue and event to evoke the world that had shaped him. Beneath the comedy and the almost kindly satire of these early works there are glimpses of the bleak view of human existence and effort and self- fictionalising that were to become the key themes and motifs of his later work.

The first of his 14 non-fiction works, The Middle Passage (1962), was a lively if unsparing report on West Indian societies as “half-made societies that seemed doomed to remain half-made” because they lacked the self-knowledge or the will to reinvent themselves in the independence period. By 1970, the urge to express ideas and opinions about a world growing everywhere more unstable and insecure began to take hold.

He admired journalism (the occupation of his father, Seepersad Naipaul) because it was much better than the novel at keeping up realistically with the changing world. To widen his net he started to shape combinations (In a Free State, 1971), hybrids (The Enigma of Arrival, 1987), and “sequences” (A Way in the World, 1994) that blurred distinctions between fiction and non-fiction.

The Middle Passage (tame in hindsight) was follow- ed by frequent travel and more on-the-spot coverage of peoples and countries in turmoil. The liberties he was to take with language registers and genres, and his ability to evoke different settings, are displayed with aplomb in In a Free State, a pageant of placelessness and insecurity that won him the Booker prize in 1971.

Of his 29 books, at least seven are likely to endure: his first collection of stories, Miguel Street (1959); the three novels A House for Mr Biswas (1961), The Mimic Men (1967) and A Bend in the River (1978); a work of non-fiction, The Loss of El Dorado (1969), an original and challenging historical work on the making of Trinidad and its polyglot capital, Port of Spain, that Naipaul described as “the synthesis of the worlds and cultures that had made me”; the global fiction In a Free State; and the ambitious The Enigma of Arrival, part autobiography, part fiction, part meditation on life, time, death and the writing life.

In these works, he created palpable geographical, social and cultural contexts in which to locate people, their stories and their emotions; and in all of them, symbolism and ideas of universal import spring unforced out of realistically rendered detail.

The scholarship in The Loss of El Dorado added conviction to the key Naipaulian preoccupation with the futility of human effort and the perils of the impossible dream. Much of his experience as a student at Oxford and as an anxious inhabitant of London in the 1950s was filtered into the constitution of Ralph Singh, the narrating character of The Mimic Men. In this novel, the miscellaneous collection of misfits and refugees with whom Singh associates for a time were soon to become a conscious part of Naipaul’s vision of a restless world of people cut off from the landscapes of their birth and not able to find purchase somewhere else. He was the first writer to stumble upon this theme and he took it further than anybody else.

His native island, the former British colony of Trinidad, with its extraordinary meeting of peoples and cultures, was his seedbed. Long after he decided he would never live in Trinidad and Tobago, he could still say: “From the writing point of view, this land is pure gold … Pure, pure gold.” Trinidad made and haunted the writer, and the evidence is in many of his books.

Born in Chaguanas, on Trinidad’s west coast, south of Port of Spain, Vidia was the second of the seven children of Seepersad and his wife, Droapatie (nee Capildeo). They were married in 1929, the year that Seepersad began his journalistic career as the Chaguanas correspondent of the Trinidad Guardian. Vidia’s early childhood was mostly spent in or near the Capildeo family residence known as the Lion House, a unique example of North Indian architecture that dominated the main street of Chaguanas, a country town in the sugar belt where the majority of Trinidad Indians lived. Seepersad quickly felt his individuality threatened by the communal life of the Capildeos. The acute tensions of this period would have been felt by his son.

When the chance came in 1938 to work in Port of Spain, as a full-time reporter with the Trinidad Guardian, Seepersad left Chaguanas to occupy rooms in a Capildeo house in Luis Street, in the Woodbrook district. The move in 1938 introduced the six-year-old Vidia to the life of the street, the pleasures and sights of the city, and in due course to the cinema, all of which were to inform the comic and compassionate stories and sketches of Miguel Street.

From 1938 to 1942, Vidia was a pupil at Tranquillity boys’ school, after which he began his “sound colonial education” at Queen’s Royal college, the country’s oldest and most British secondary school. At the same time, he witnessed his father working at being a writer, self-publishing in 1943 a remarkable collection of stories, Gurudeva and Other Indian Tales. “I loved them as writing, as well as for the labour I had seen going into their making.”

Seepersad’s example made it possible for a young boy in a colony to dream of a literary career. The purchase of a house of his own in 1946 brought much needed relief to Seepersad. To Vidia, in his last two years at QRC, and to the family, it brought peace and desperately needed stability.

In 1950, Naipaul went to University College, Oxford, to study English and become a writer. Five years later, he married Patricia Hale, who would be the one reliable element in his life for 41 years until her death. Pat may not have been his muse but she remained in all seasons note-taker, sounding board, listener to drafts, common reader and excited fan.

A stillborn first novel as well as book-reviewing for the New Statesman would have made it clear enough that Naipaul did not really want to be (could not be) the kind of writer envisaged by the raw 18-year-old in The Enigma of Arrival.

The example of Seepersad’s book, and the older man’s constant recommendation of West Indian raw material were reinforced by the years Naipaul spent as editor of the BBC’S Caribbean Voices programme, reading hundreds of manuscripts from the islands and sharing fellowship with the writers hanging out in the freelancers’ room at the BBC.

When he started to turn to his natural raw material, it was to three of those writers, the Caribbean Andrew Salkey and Gordon Woolford and an Englishman, John Stockbridge, that he excitedly ran with what became the opening story of Miguel Street: “Without that fellowship, without the response of the three men who read the story, I might not have wanted to go on.” After the breakthrough, he produced The Mystic Masseur (1957) and The Suffrage of Elvira (1958) in quick time and then tussled with his demons for three years to land his greatest work, A House for Mr Biswas.

In London in 1958, in a time of different stresses, he was able to go back in memory to the traumas of life in the Lion House and to the years in Woodbrook as raw material for his masterpiece. The three-generational novel depicts the exposure of descend- ants of Indians to the shifting society of Trinidad and describes their evolution from 1906 to 1953. Comic richness arises from the battles between Mr Biswas and his in-laws, and the manic journalism of the main character, who, like his prototype, Seepersad Naipaul, works on the city newspaper. Mr Biswas saw that the world is what it is and refused to allow himself to be nothing.

Naipaul was well regarded for his travel books and for innovations in the genre of travel writing, and spoke of valuing them above his novels, an opinion that few readers would endorse. He travelled to the Americas, Africa, India, Mauritius, Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan and every corner of the earth touched by invader or coloniser to report on failed and failing states and to expose what he regarded as the malformed or undeveloped selves in them. He stocked his “travel” books with character, scene and dialogue and rendered episodes.

He wanted Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions Among the Converted Peoples (1998) to be thought of as a book of people and stories unshaped by the writer’s opinions, but opinion and idea dominated his later work. His topics included imperialism, freedom, emergent nationalisms, religion, revolution, fundamentalism and the colonial mentality. He saw the terror waiting to be unleashed upon the world by half-baked revolutions, mutinies and holy wars, and by fundamentalism and fanaticism of any kind. By the 1990s he had made himself the cynical poet of post-imperialism and the peculiar prophet of violence, global disorientation and homelessness. He was considered by many to be the first modern global writer.

His fellow West Indians began having difficulties with Naipaul early in his career. He was accused of writing “castrated satire”. A sentence in The Middle Passage that “history is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was ever created in the West Indies” has been held unforgivingly as proof that he was anti-West Indian. He has been accused of racial prejudice against people of African origin, for saying that Africa has no future, and for presenting women negatively.

In interviews he seemed to go out of his way to provoke. He remained unchastened, and his detractors continued reading him, watching for what came next. In 1983, a taxi-driver at Piarco airport in Trinidad pulled him aside and asked: “You is Naipaul?” When he owned up to the name the driver looked at him with compassion: “Look, you better travel with me, yes. We don’t like you down here at all.” He told this story with delight. Although he was severe on the US and Britain, it was his harsh accounts of India, the Islamic world and former imperial possessions that led to his being denounced as a spokesman for the west against developing cultures and societies.

In 2008, he gave fuel to his critics by allowing an authorised biography, The World Is What It Is, by Patrick French, to publicise bold confessions about his visits to prostitutes, intimate details of his obnoxious behaviour towards Pat and his mistress, Margaret Gooding, and many of the cruelties attending his relationships with them and other people. He acted as if he did not care. He would sacrifice anyone or anything for his vocation.

He saw himself as a man without a place. With The Middle Passage, Naipaul had effectively written off Trinidad and the West Indies as places to live. After writing An Area of Darkness (1964), he knew that whatever it might mean to him, India was not home. Within months of the publication of The Mimic Men, the life he had been constructing for himself as a literary figure in the UK was shaken by Britain’s new immigration laws.

He wrote to a friend about “a very special chaos” he felt coming to Britain, and reported feeling that “I could no longer stay here.” He flirted briefly with the idea of living in Trinidad. In July 1968 he and his wife were settling in Canada, but by September had changed their minds and returned to the UK. It was at this time that Naipaul completed In a Free State, an overwhelming map of dislocation, of fractured worlds, and of damaged individuals in a violent free state. In the prologue, a crazed and lonely old man avows that he is a citizen of the world; and the epilogue closes with the image of defeated soldiers “lost, trying to walk back home, casting long shadows on the sand”.

At the end of 1970 Naipaul’s friends rescued him from his own dislocation. A bungalow on the grounds of Wilsford Manor in Wiltshire was secured for him at a minimal rent, and after 11 years as tenants there, the Naipauls moved into their own house, Dairy Cottage.

His life from 1972 to 1995 was dominated by a triangular relationship with Pat, who stayed at home, and Gooding, an Argentinian woman whom Naipaul met in Buenos Aires in 1972. Their tempestuous affair was conducted in several continents for more than 20 years, and was terminated abruptly by Naipaul only in 1995, when Pat was dying of cancer and he met and proposed to Nadira Khannum Alvi in Pakistan. He received in this period almost every major literary award and recognition, including a knighthood in 1990. He established himself as a phenomenon and a spectacle, “the writer” personified.

His outstanding work of this period was A Bend in the River, a real novel issuing from a novelist possessed. It is Naipaul’s most frightening presentation of a world without meaning or the possibility of meaning. Meaninglessness and ineffectuality became his subject in Half a Life (2001) and Magic Seeds (2004), which pick dispassionately through the unremarkable life of Willie Chandran, from India to London to Africa to India, and back again to London, making an epic of nonentity and purposelessness. Naipaul secretes into them elements from earlier books and his own life in London as if to remind us how fragile are the foundations, and against what dispiriting odds anything is achieved in the world.

The World Is What It Is was a fitting title for the biography of a writer who struggled all his life between poles. On the one hand, there was social and personal anomie, on the other a commitment to vocation. He had a mutated Hindu view that all the world was illusion and only the self was real, and yet his writing showed him observing and reporting the external world with precision. He was a difficult man to get to know.

His meaning for the island of his birth, and for the world after the centuries of empires and colonies, “everything of value”, as he put it in his Nobel lecture, was in his books: “I am the sum of my books.” In time, that will be seen as his most appropriate epitaph.

In 1996 he married Nadira. She survives him, along with their daughter, Maleeha, and his sisters Mira, Savi and Nalini.

• Vidia (Vidiadhar) Surajprasad Naipaul, writer, born 17 August 1932; died 11 August 2018

Elegy for V.S. Naipaul (1932-2018)

We sometimes see the past and then ponder

as if it flares up in heat like bon fire.

We scurry, wafting flames destroying us

narcissistic of colour omnibus.

We root our culture clothed in slavery

and embrace indentureship crockery.

Then we stand firm, indignant to a bone

and so embrace a new norm, not alone.

Our independence did not set us free

but craft our British mold sacrality.

~ Leonard Dabydeen

Member of The Society of Classical Poets

Author: Watching You, A Collection of Tetractys Poems (2012)

Searching for You, A Collection of Tetractys and Fibonacci Poems (2015)

LikeLike