A review by Stephen Clark for AFR Weekend.

It’s hard to imagine what more plants could do for humans than they have already. They have clothed us, housed us and fed us. Without plants there would be no salve, no cure, for a plenitude of diseases and injuries. They gave us our first economic bubble (Dutch tulips, 1630s) and our first visions of the divine (hallucinogens and opioids, time immemorial).

The short, fragrant lives of flowers fill us with joy, and artists use depictions of plants to celebrate nature’s bounty and remind us of the inexorable cycle of growth and decay. At the asylum of Saint-Remy in 1889, Vincent van Gogh calmed himself by drawing “a blade of grass, a pine tree branch, an ear of wheat”. Monet, of course, had his waterlilies.

Botanical illustration is different to art. Knowledge is the goal: although artistic imagination is required. It was Leonardo da Vinci in the 1500s who observed that tree rings showed a tree’s age, a key step towards carbon dating. When he concluded that the differing width of the rings was related to “those years that were moister or dryer”, climate science was born.

Botanists were essential to the age of exploration. For one thing, knowing which plants to eat and which to avoid is crucial to survival. It was their journals filled with drawings of new species that ultimately directed settlement, farming and trade. Whole countries were named for their botany. Brazil, for example, was named after the brazilwood tree. Trade in crops of sugar, tobacco, cotton and coffee gave rise to the system we call globalisation.

A spirit of scientific inquiry gripped Europe as New World plants flooded in from the colonies. A Caribbean pineapple, sketched by Spanish explorer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in 1547, demonstrates this mania for the exotic. As a kind of bonus, the pineapple’s row of scales also proved the existence of the Fibonacci mathematical sequence, first posited in the Middle Ages.

The species name of Lepidozia reptans means “crawling” and refers to the way this tiny moss-like plant creeps and spreads over rotting bark and moist rock faces. Seen through a microscope the branches – this primitive species has no roots or flowers – reach out like minute hands covered in reptilian armour.

Microphotography is a relatively new step in our long study of plants, beginning when our ancestors first cultivated seeds 12,000 years ago. To contemplate a frieze of red Minoan lilies waving in the Santorini breeze, painted in 1600BC, is to acknowledge the deep aesthetic pleasure we also reap from plants, our oldest and best allies on this planet.

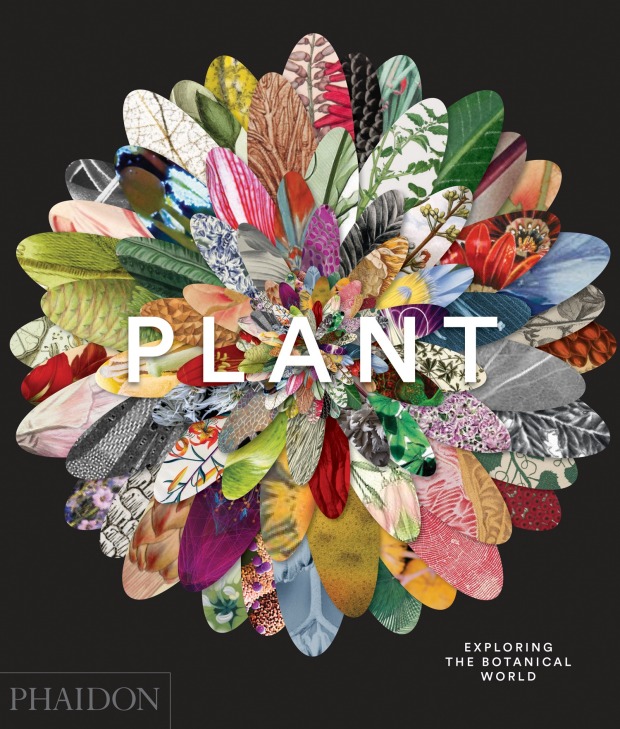

Plant: Exploring the Botanical World, Phaidon Press, $79.95